'44th Street'

'44th Street'

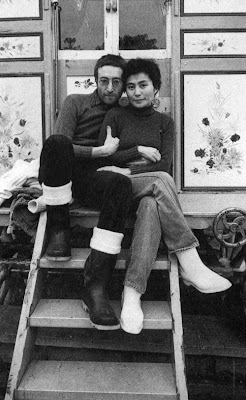

NYC 1980

By David Sheff

September 8-28, 1980

PLAYBOY: "A Day in the Life."LENNON: Just as it sounds: I was reading the paper one day and I noticed two stories. One was the Guinness heir who killed himself in a car. That was the main headline story. He died in London in a car crash. On the next page was a story about 4000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire. In the streets, that is. They were going to fill them all. Paul's contribution was the beautiful little lick in the song "I'd love to turn you on." I had the bulk of the song and the words, but he contributed this little lick floating around in his head that he couldn't use for anything. I thought it was a damn good piece of work. PLAYBOY: May we continue with some of the ones that seem more personal and see what reminiscences they inspire? LENNON: Reminisce away. PLAYBOY: For no reason whatsoever, let's start with "I Wanna Be Your Man." LENNON: Paul and I finished that one off for the Stones. We were taken down by Brian to meet them at the club where they were playing in Richmond. They wanted a song and we went to see what kind of stuff they did. Paul had this bit of a song and we played it roughly for them and they said, "Yeah, OK, that's our style." But it was only really a lick, so Paul and I went off in the corner of the room and finished the song off while they were all sitting there, talking. We came back and Mick and Keith said, "Jesus, look at that. They just went over there and wrote it." You know, right in front of their eyes. We gave it to them. It was a throwaway. Ringo sang it for us and the Stones did their version. It shows how much importance we put on them. We weren't going to give them anything great, right? That was the Stones' first record. Anyway, Mick and Keith said, "If they can write a song so easily, we should try it." They say it inspired them to start writing together. PLAYBOY: How about "Strawberry FieldsForever?" LENNON: Strawberry Fields is a real place. After I stopped living at Penny Lane, I moved in with my auntie who lived in the suburbs in a nice semidetached place with a small garden and doctors and lawyers and that ilk living around - - not the poor slummy kind of image that was projected in all the Beatles stories. In the class system, it was about half a class higher than Paul, George and Ringo, who lived in government-subsidized housing. We owned our house and had a garden. They didn't have anything like that. Near that home was Strawberry Fields, a house near a boys' reformatory where I used to go to garden parties as a kid with my friends Nigel and Pete. We would go there and hang out and sell lemonade bottles for a penny. We always had fun at Strawberry Fields. So that's where I got the name. But I used it as an image. Strawberry Fields forever. PLAYBOY: And the lyrics, for instance: "Living is easy---- " LENNON: [Singing] "With eyes closed. Misunderstanding all you see." It still goes, doesn't it? Aren't I saying exactly the same thing now? The awareness apparently trying to be expressed is -- let's say in one way I was always hip. I was hip in kindergarten. I was different from the others. I was different all my life. The second verse goes, "No one I think is in my tree." Well, I was too shy and self-doubting. Nobody seems to be as hip as me is what I was saying. Therefore, I must be crazy or a genius -- "I mean it must be high or low," the next line. There was something wrong with me, I thought, because I seemed to see things other people didn't see. I thought I was crazy or an egomaniac for claiming to see things other people didn't see. As a child, I would say, "But this is going on!" and everybody would look at me as if I was crazy. I always was so psychic or intuitive or poetic or whatever you want to call it, that I was always seeing things in a hallucinatory way. It was scary as a child, because there was nobody to relate to. Neither my auntie nor my friends nor anybody could ever see what I did. It was very, very scary and the only contact I had was reading about an Oscar Wilde or a Dylan Thomas or a Vincent van Gogh -- all those books that my auntie had that talked about their suffering because of their visions. Because of what they saw, they were tortured by society for trying to express what they were. I saw loneliness. PLAYBOY: Were you able to find others to share your visions with? LENNON: Only dead people in books. Lewis Carroll, certain paintings. Surrealism had a great effect on me, because then I realized that my imagery and my mind wasn't insanity; that if it was insane, I belong in an exclusive club that sees the world in those terms. Surrealism to me is reality. Psychic vision to me is reality. Even as a child. When I looked at myself in the mirror or when I was 12, 13, I used to literally trance out into alpha. I didn't know what it was called then. I found out years later there is a name for those conditions. But I would find myself seeing hallucinatory images of my face changing and becoming cosmic and complete. It caused me to always be a rebel. This thing gave me a chip on the shoulder; but, on the other hand, I wanted to be loved and accepted. Part of me would like to be accepted by all facets of society and not be this loudmouthed lunatic musician. But I cannot be what I am not. Because of my attitude, all the other boys' parents, including Paul's father, would say, "Keep away from him." The parents instinctively recognized what I was, which was a troublemaker, meaning I did not conform and I would influence their kids, which I did. I did my best to disrupt every friend's home I had. Partly, maybe, it was out of envy that I didn't have this so-called home. But I really did. I had an auntie and an uncle and a nice suburban home, thank you very much. Hear this, Auntie. She was hurt by a remark Paul made recently that the reason I am staying home with Sean now is because I never had a family life. It's absolute rubbish. There were five women who were my family. Five strong, intelligent women. Five sisters. One happened to be my mother. My mother was the youngest. She just couldn't deal with life. She had a husband who ran away to sea and the war was on and she couldn't cope with me, and when I was four and a half, I ended up living with her elder sister. Now, those women were fantastic. One day I might do a kind of "Forsyte Saga" just about them. That was my first feminist education. Anyway, that knowledge and the fact that I wasn't with my parents made me see that parents are not gods. I would infiltrate the other boys' minds. Paul's parents were terrified of me and my influence, simply because I was free from the parents' strangle hold. That was the gift I got for not having parents. I cried a lot about not having them and it was torture, but it also gave me an awareness early. I wasn't an orphan, though. My mother was alive and lived a 15-minute walk away from me all my life. I saw her off and on. I just didn't live with her. PLAYBOY: Is she alive? LENNON: No, she got killed by an off-duty cop who was drunk after visiting my auntie's house where I lived. I wasn't there at the time. She was just at a bus stop. I was 16. That was another big trauma for me. I lost her twice. When I was five and I moved in with my auntie, and then when she physically died. That made me more bitter; the chip on my shoulder I had as a youth got really big then. I was just really re-establishing the relationship with her and she was killed. PLAYBOY: Her name was Julia, wasn't it? Is she the Julia of your song of that name on "The White Album?" LENNON: The song is for her -- and for Yoko. PLAYBOY: What kind of relationship did you have with your father, who went away to sea? Did you ever see him again? LENNON: I never saw him again until I made a lot of money and he came back. PLAYBOY: How old were you? LENNON: Twenty-four or 25. I opened the "Daily Express" and there he was, washing dishes in a small hotel or something very near where I was living in the Stockbroker belt outside London. He had been writing to me to try to get in contact. I didn't want to see him. I was too upset about what he'd done to me and to my mother and that he would turn up when I was rich and famous and not bother turning up before. So I wasn't going to see him at all, but he sort of blackmailed me in the press by saying all this about being a poor man washing dishes while I was living in luxury. I fell for it and saw him and we had some kind of relationship. He died a few years later of cancer. But at 65, he married a secretary who had been working for the Beatles, age 22, and they had a child, which I thought was hopeful for a man who had lived his life as a drunk and almost a Bowery bum. PLAYBOY: We'll never listen to "Strawberry Fields Forever" the same way again. What memories are jogged by the song "Help!?" LENNON: When "Help!" came out in '65, I was actually crying out for help. Most people think it's just a fast rock-'n'-roll song. I didn't realize it at the time; I just wrote the song because I was commissioned to write it for the movie. But later, I knew I really was crying out for help. It was my fat Elvis period. You see the movie: He -- I -- is very fat, very insecure, and he's completely lost himself. And I am singing about when I was so much younger and all the rest, looking back at how easy it was. Now I may be very positive -- yes, yes -- but I also go through deep depressions where I would like to jump out the window, you know. It becomes easier to deal with as I get older; I don't know whether you learn control or, when you grow up, you calm down a little. Anyway, I was fat and depressed and I was crying out for help. In those days, when the Beatles were depressed, we had this little chant. I would yell out, "Where are we going, fellows?" They would say, "To the top, Johnny," in pseudo- American voices. And I would say, "Where is that, fellows?" And they would say, "To the toppermost of the poppermost." It was some dumb expression from a cheap movie -- a la "Blackboard Jungle" -- about Liverpool. Johnny was the leader of the gang. PLAYBOY: What were you depressed about during the "Help!" period? LENNON: The Beatles thing had just gone beyond comprehension. We were smoking marijuana for breakfast. We were well into marijuana and nobody could communicate with us, because we were just all glazed eyes, giggling all the time. In our own world. That was the song, "Help!." I think everything that comes out of a song -- even Paul's songs now, which are apparently about nothing -- shows something about yourself. PLAYBOY: Was "I'm a Loser" a similarly personal statement? LENNON: Part of me suspects that I'm a loser and the other part of me thinks I'm God Almighty. PLAYBOY: How about "Cold Turkey?" LENNON: The song is self-explanatory. The song got banned, even though it's antidrug. They're so stupid about drugs, you know. They're not looking at the cause of the drug problem: Why do people take drugs? To escape from what? Is life so terrible? Are we living in such a terrible situation that we can't do anything without reinforcement of alcohol, tobacco? Aspirins, sleeping pills, uppers, downers, never mind the heroin and cocaine -- they're just the outer fringes of Librium and speed. PLAYBOY: Do you use any drugs now? LENNON: Not really. If somebody gives me a joint, I might smoke it, but I don't go after it. PLAYBOY: Cocaine? LENNON: I've had cocaine, but I don't like it. The Beatles had lots of it in their day, but it's a dumb drug, because you have to have another one 20 minutes later. Your whole concentration goes on getting the next fix. Really, I find caffeine is easier to deal with. PLAYBOY: Acid? LENNON: Not in years. A little mushroom or peyote is not beyond my scope, you know, maybe twice a year or something. You don't hear about it anymore, but people are still visiting the cosmos. We must always remember to thank the CIA and the Army for LSD. That's what people forget. Everything is the opposite of what it is, isn't it, Harry? So get out the bottle, boy -- and relax. They invented LSD to control people and what they did was give us freedom. Sometimes it works in mysterious ways its wonders to perform. If you look in the Government reports on acid, the ones who jumped out the window or killed themselves because of it, I think even with Art Linkletter's daughter, it happened to her years later. So, let's face it, she wasn't really on acid when she jumped out the window. And I've never met anybody who's had a flashback on acid. I've never had a flashback in my life and I took millions of trips in the Sixties. PLAYBOY: What does your diet include besides sashimi and sushi, Hershey bars and cappuccinos? LENNON: We're mostly macrobiotic, but sometimes I take the family out for a pizza. ONO: Intuition tells you what to eat. It's dangerous to try to unify things. Everybody has different needs. We went through vegetarianism and macrobiotic, but now, because we're in the studio, we do eat some junk food. We're trying to stick to macrobiotic: fish and rice, whole grains. You balance foods and eat foods indigenous to the area. Corn is the grain from this area. PLAYBOY: And you both smoke up a storm. LENNON: Macrobiotic people don't believe in the big C. Whether you take that as a rationalization or not, macrobiotics don't believe that smoking is bad for you. Of course, if we die, we're wrong. PLAYBOY: Let's go back to jogging your memory with songs. How about Paul's song "Hey Jude?" LENNON: He said it was written about Julian. He knew I was splitting with Cyn and leaving Julian then. He was driving to see Julian to say hello. He had been like an uncle. And he came up with "Hey Jude." But I always heard it as a song to me. Now I'm sounding like one of those fans reading things into it. . . . Think about it: Yoko had just come into the picture. He is saying. "Hey, Jude" -- "Hey, John." Subconsciously, he was saying, Go ahead, leave me. On a conscious level, he didn't want me to go ahead. The angel in him was saying. "Bless you." The Devil in him didn't like it at all, because he didn't want to lose his partner. PLAYBOY: What about "Because?" LENNON: I was lying on the sofa in our house, listening to Yoko play Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata" on the piano. Suddenly, I said, "Can you play those chords backward?" She did, and I wrote "Because" around them. The song sounds like "Moonlight Sonata," too. The lyrics are clear, no bullshit, no imagery, no obscure references. PLAYBOY: "Give Peace a Chance." LENNON: All we were saying was give peace a chance. PLAYBOY: Was it really a Lennon-McCartney composition? LENNON: No, I don't even know why his name was on it. It's there because I kind of felt guilty because I'd made the separate single -- the first -- and I was really breaking away from the Beatles. PLAYBOY: Why were the compositions you and Paul did separately attributed to Lennon-McCartney? LENNON: Paul and I made a deal when we were 15. There was never a legal deal between us, just a deal we made when we decided to write together that we put both our names on it, no matter what. PLAYBOY: How about "Do You Want to Know a Secret?" LENNON: The idea came from this thing my mother used to sing to me when I was one or two years old, when she was still living with me. It was from a Disney movie: "Do you want to know a secret? Promise not to tell/You are standing by a wishing well." So, with that in my head, I wrote the song and just gave it to George to sing. I thought it would be a good vehicle for him, because it had only three notes and he wasn't the best singer in the world. He has improved a lot since then; but in those days, his ability was very poor. I gave it to him just to give him a piece of the action. That's another reason why I was hurt by his book. I even went to the trouble of making sure he got the B side of a Beatles single, because he hadn't had a B side of one until "Do You Want to Know a Secret?" "Something" was the first time he ever got an A side, because Paul and I always wrote both sides. That wasn't because we were keeping him out but simply because his material was not up to scratch. I made sure he got the B side of "Something," too, so he got the cash. Those little things he doesn't remember. I always felt bad that George and Ringo didn't get a piece of the publishing. When the opportunity came to give them five percent each of Maclen, it was because of me they got it. It was not because of Klein and not because of Paul but because of me. When I said they should get it, Paul couldn't say no. I don't get a piece of any of George's songs or Ringo's. I never asked for anything for the contributions I made to George's songs like "Taxman." Not even the recognition. And that is why I might have sounded resentful about George and Ringo, because it was after all those things that the attitude of "John has forsaken us" and "John is tricking us" came out -- which is not true. PLAYBOY: "Happiness Is a Warm Gun." LENNON: No, it's not about heroin. A gun magazine was sitting there with a smoking gun on the cover and an article that I never read inside called "Happiness Is a Warm Gun." I took it right from there. I took it as the terrible idea of just having shot some animal. PLAYBOY: What about the sexual puns: "When you feel my finger on your trigger"? LENNON: Well, it was at the beginning of my relationship with Yoko and I was very sexually oriented then. When we weren't in the studio, we were in bed. PLAYBOY: What was the allusion to "Mother Superior jumps the gun"? LENNON: I call Yoko Mother or Madam just in an offhand way. The rest doesn't mean anything. It's just images of her. PLAYBOY: "Across the Universe." LENNON: The Beatles didn't make a good record of "Across the Universe." I think subconsciously we -- I thought Paul subconsciously tried to destroy my great songs. We would play experimental games with my great pieces, like "Strawberry Fields," which I always felt was badly recorded. It worked, but it wasn't what it could have been. I allowed it, though. We would spend hours doing little, detailed cleaning up on Paul's songs, but when it came to mine -- especially a great song like "Strawberry Fields" or "Across the Universe" -- somehow an atmosphere of looseness and experimentation would come up. PLAYBOY: Sabotage? LENNON: Subconscious sabotage. I was too hurt. . . . Paul will deny it, because he has a bland face and will say this doesn't exist. This is the kind of thing I'm talking about where I was always seeing what was going on and began to think, Well, maybe I'm paranoid. But it is not paranoid. It is the absolute truth. The same thing happened to "Across the Universe." The song was never done properly. The words stand, luckily. PLAYBOY: "Getting Better." LENNON: It is a diary form of writing. All that "I used to be cruel to my woman, I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loved" was me. I used to be cruel to my woman, and physically -- any woman. I was a hitter. I couldn't express myself and I hit. I fought men and I hit women. That is why I am always on about peace, you see. It is the most violent people who go for love and peace. Everything's the opposite. But I sincerely believe in love and peace. I am not violent man who has learned not to be violent and regrets his violence. I will have to be a lot older before I can face in public how I treated women as a youngster. PLAYBOY: "Revolution." LENNON: We recorded the song twice. The Beatles were getting really tense with one another. I did the slow version and I wanted it out as a single: as a statement of the Beatles' position on Vietnam and the Beatles' position on revolution. For years, on the Beatle tours, Epstein had stopped us from saying anything about Vietnam or the war. And he wouldn't allow questions about it. But on one tour, I said, "I am going to answer about the war. We can't ignore it." I absolutely wanted the Beatles to say something. The first take of "Revolution" -- well, George and Paul were resentful and said it wasn't fast enough. Now, if you go into details of what a hit record is and isn't maybe. But the Beatles could have afforded to put out the slow, understandable version of "Revolution" as a single. Whether it was a gold record or a wooden record. But because they were so upset about the Yoko period and the fact that I was again becoming as creative and dominating as I had been in the early days, after lying fallow for a couple of years, it upset the apple cart. I was awake again and they couldn't stand it? PLAYBOY: Was it Yoko's inspiration? LENNON: She inspired all this creation in me. It wasn't that she inspired the songs; she inspired me. The statement in "Revolution" was mine. The lyrics stand today. It's still my feeling about politics. I want to see the plan. That is what I used to say to Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. Count me out if it is for violence. Don't expect me to be on the barricades unless it is with flowers. PLAYBOY: What do you think of Hoffman's turning himself in? LENNON: Well he got what he wanted. Which is to be sort of an underground hero for anybody who still worships any manifestation of the underground. I don't feel that much about it anymore. Nixon, Hoffman, it's the same. They are all from the same period. It was kind of surprising to see Abbie on TV, but it was also surprising to see Nixon on TV. Maybe people get the feeling when they see me or us. I feel, What are they doing there? Is this an old newsreel? PLAYBOY: On a new album, you close with "Hard Times Are Over (For a While)." Why? LENNON: It's not a new message: "Give Peace a Chance" -- we're not being unreasonable, just saying, "Give it a chance." With "Imagine," we're saying, "Can you imagine a world without countries or religions?" It's the same message over and over. And it's positive. PLAYBOY: How does it feel to have people anticipate your new record because they feel you are a prophet of sorts? When you returned to the studio to make "Double Fantasy," some of your fans were saying things like, "Just as Lennon defined the Sixties and the Seventies, he'll be defining the Eighties." LENNON: It's very sad. Anyway, we're not saying anything new. A, we have already said it and, B, 100,000,000 other people have said it, too. PLAYBOY: But your songs do have messages. LENNON: All we are saying is, "This is what is happening to us." We are sending postcards. I don't let it become "I am the awakened; you are sheep that will be shown the way." That is the danger of saying anything, you know. PLAYBOY: Especially for you. LENNON: Listen, there's nothing wrong with following examples. We can have figure heads and people we admire, but we don't need leaders. "Don't follow leaders, watch the parking meters." PLAYBOY: You're quoting one of your peers, of sorts. Is it distressing to you that Dylan is a born-again Christian? LENNON: I don't like to comment on it. For whatever reason he's doing it, it is personal for him and he needs to do it. But the whole religion business suffers from the "Onward, Christian Soldiers" bit. There's too much talk about soldiers and marching and converting. I'm not pushing Buddhism, because I'm no more a Buddhist than I am a Christian, but there's one thing I admire about the religion: There's no proselytizing. PLAYBOY: Were you a Dylan fan? LENNON: No, I stopped listening to Dylan with both ears after "Highway 64" [sic] and "Blonde on Blonde," and even then it was because George would sit me down and make me listen. PLAYBOY: Like Dylan, weren't you also looking for some kind of leader when you did primal-scream therapy with Arthur Janov? ONO: I think Janov was a daddy for John. I think he has this father complex and he's always searching for a daddy. LENNON: Had, dear. I had a father complex. PLAYBOY: Would you explain? ONO: I had a daddy, a real daddy, sort of a big and strong father like a Billy Graham, but growing up, I saw his weak side. I saw the hypocrisy. So whenever I see something that is supposed to be so big and wonderful -- a guru or primal scream -- I'm very cynical. LENNON: She fought with Janov all the time. He couldn't deal with it. ONO: I'm not searching for the big daddy. I look for something else in men -- something that is tender and weak and I feel like I want to help. LENNON: And I was the lucky cripple she chose! ONO: I have this mother instinct, or whatever. But I was not hung up on finding a father, because I had one who disillusioned me. John never had a chance to get disillusioned about his father, since his father wasn't around, so he never thought of him as that big man. PLAYBOY: Do you agree with that assessment, John? LENNON: A lot of us are looking for fathers. Mine was physically not there. Most people's are not there mentally and physically, like always at the office or busy with other things. So all these leaders, parking meters, are all substitute fathers, whether they be religious or political. . . . All this bit about electing a President. We pick our own daddy out of a dog pound of daddies. This is the daddy that looks like the daddy in the commercials. He's got the nice gray hair and the right teeth and the parting's on the right side. OK? This is the daddy we choose. The dog pound of daddies, which is the political arena, gives us a President, then we put him on a platform and start punishing him and screaming at him because Daddy can't do miracles. Daddy doesn't heal us. PLAYBOY: So Janov was a daddy for you. Who else? ONO: Before, there was Maharishi. LENNON: Maharishi was a father figure, Elvis Presley might have been a father figure. I don't know. Robert Mitchum. Any male image is a father figure. There's nothing wrong with it until you give them the right to give you sort of a recipe for your life. What happens is somebody comes along with a good piece of truth. Instead of the truth's being looked at, the person who brought it is looked at. The messenger is worshiped, instead of the message. So there would be Christianity, Mohammedanism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Marxism, Maoism -- everything -- it is always about a person and never about what he says. ONO: All the isms are daddies. It's sad that society is structured in such a way that people cannot really open up to each other, and therefore they need a certain theater to go to to cry or something like that. LENNON: Well, you went to est. ONO: Yes, I wanted to check it out. LENNON: We went to Janov for the same reason. ONO: But est people are given a reminder---- LENNON: Yeah, but I wouldn't go and sit in a room and not pee. ONO: Well, you did in primal scream. LENNON: Oh, but I had you with me. ONO: Anyway, when I went to est, I saw Werner Erhardt, the same thing. He's a nice showman and he's got a nice gig there. I felt the same thing when we went to Sai Baba in India. In India, you have to be a guru instead of a pop star. Guru is the pop star of India and pop star is the guru here. LENNON: But nobody's perfect, etc., etc. Whether it's Janov or Erhardt or Maharishi or a Beatle. That doesn't take away from their message. It's like learning how to swim. The swimming is fine. But forget about the teacher. If the Beatles had a message, it was that. With the Beatles, the records are the point, not the Beatles as individuals. You don't need the package, just as you don't need the Christian package or the Marxist package to get the message. People always got the image I was an anti-Christ or antireligion. I'm not. I'm a most religious fellow. I was brought up a Christian and I only now understand some of the things that Christ was saying in those parables. Because people got hooked on the teacher and missed the message. PLAYBOY: And the Beatles taught people how to swim? LENNON: If the Beatles or the Sixties had a message, it was to learn to swim. Period. And once you learn to swim, swim. The people who are hung up on the Beatles' and the Sixties' dream missed the whole point when the Beatles' and the Sixties' dream became the point. Carrying the Beatles' or the Sixties' dream around all your life is like carrying the Second World War and Glenn Miller around. That's not to say you can't enjoy Glenn Miller or the Beatles, but to live in that dream is the twilight zone. It's not living now. It's an illusion.